THE LEAGUE OF EXTRAORDINARY GENTLEMEN (2003)

Peta Wilson is LXG’s Mina Harker. The Australian actress

and model can next be seen in SUPERMAN RETURNS,

in the dizzying role as "flight attendant."

and model can next be seen in SUPERMAN RETURNS,

in the dizzying role as "flight attendant."

WHAT is known today as Steampunk has its beginnings in the Victorian penny dreadfuls and the novels of Jules Verne; an increasingly literate public took advantage of the opportunities for adventure and high romance offered them by Verne, Wells, Haggard, Conan Doyle and Burroughs, as well as the macabre tales of Poe and Hawthorne. Steampunk, is in part, a nostalgic reclamation of Victorian and Edwardian Scientific Romances, Imperialist derring-do and Gothic horrors, reminiscing about a more elegant age that never really existed. Yet the spectre of the Victorian era has never left the discourse of the fantastic for very long; new creators always find themselves returning to this steam-driven crucible, an age of tremendous aesthetic decadence yet sublime heavy industry.

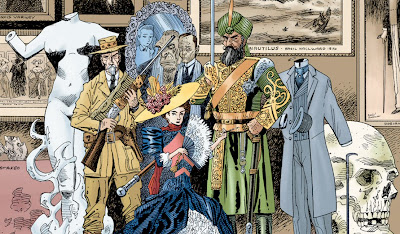

The mannerisms and references Alan Moore drops into his comic book series The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen makes it a veritable Steampunk bible. Previously, the Northampton writer has subverted and reinvented myths about superheroes (Watchmen) and Jack the Ripper (From Hell), and this time he’s taken it further by pulling literature into the graphic medium like never before. Illustrated by Kevin O’Neill, the series is a homage to the grand adventure stories of yesteryear, with a dark slant that only Moore could envision. By applying the conventions of the superhero team-up book to characters of Victorian literature – Mina Murray from Dracula, Allan Quatermain, Captain Nemo, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and The Invisible Man all acting under the auspices of the British Secret Service – the scenario recreates the reading experiences and entertainment we had as children. But we have the best of both worlds – a youthful sense of wonder and a mature reflection upon it.

The League are recognisable characters, not just visually but in terms of their literary and cultural reputations. Beyond that Western readers know them because they represent archetypal characters from Victorian literature, archetypes that are still present in popular culture.

The typical Moore twist is that each of the characters are presented as being somewhat past their prime, and well past their individually known stories. Quatermain, for instance, is rescued from an opium den and a life of dissolution, and Wilhemina Murray, formerly Mina Harker - erstwhile wife of the ill-fated Jonathan Harker - continually conceals her neck after incidents which left her ravaged by a foreign nobleman (i.e. Count Dracula), thus setting her outside of polite society. Therefore, this is not a gathering of squeaky clean heroic individuals, which makes them all the more interesting. With Quatermain an addict, Dr Jekyll threatening to change into Mr Hyde at any stressful moment, and The Invisible Man remaining completely amoral, things are never straightforward.

Moore and O’Neill evidently revel in this new pulp universe. The idea of a Victorian League is just a starting point, with the creative team tirelessly working in the era’s architectural fancies into their fantasy environment. The fact that all characters or names refereed in the strip would have their origin in either fictions written during or before the period in hand, or else in elements from later works that could be retro-engineered into a continuity, has made the series popular with normally non-comic book fans, including Sherlockians and the H. Rider Haggard Appreciation Society. O’Neill renders an intricate world of Empire at its zenith emerging from the filth and squalor of an authentic 19th Century London; his scratchy style is particularly effective with Hyde and Nemo, portraying a brutish appearance and imposing filed fangs for the former, and an appropriate burning gaze for the latter. His pencils are often cartoonish but always precise and full of motion and expression, lending each character, no matter how trivial, a unique sense of personality.

The first volume of stories centre around an amount of Cavorite being stolen by a nefarious crime lord, while the second series is set amongst H.G. Wells’ Martian invasion. Depicted here is the Question Mark Man, a trademark from the first series who tends to have been replaced by a Boadicea figure in the second. In both instances, the symbols resonate with a bygone era.

This freshness make Stephen Norrington’ 2003 film adaptation even more depressing, despite some astounding set design by Carol Spier. Typically known as LXG, this abomination, starring Sean Connery as Quatermain, starts exploding in your face almost immediately. The movie brings the characters together to battle a supervillain called the Fantom, but uses them like guest stars in some variety show. As we watch, often dumbstruck, Dorian Gray (Stuart Townsend) minces around trying to hide his portrait, and The Invisible Man (Guy Skinner) literally disappears for huge stretches and then reappears with the same annoying cockney accent and bad jokes. And in Venice, where the narrow canals can accommodate the Nautilus, the Fantom's men detonate explosions in the middle of a carnival, while our heroes - who now include Mississippi River ragamuffin Tom Sawyer (Shane West) for American interest - race around in a white limousine.